Explore the chilling story of Kuru, the “Laughing Death,” its cultural origins, scientific discoveries, and global lessons learned.

“Don’t feel like reading? Immerse yourself in the chilling tale through our audiobook version—just hit play and let the story unfold!” 👇👇👇

Introduction

Deep within the lush, tropical forests of Papua New Guinea lies one of the most haunting mysteries in medical history. In the 1950s, an isolated community called the Fore tribe became the epicenter of a chilling epidemic, one that baffled scientists and terrified its victims. The disease, known as Kuru, earned the grim moniker “The Laughing Death” due to its unusual symptoms—uncontrollable laughter, tremors, and eventual death. What made Kuru so enigmatic was its association with the tribe’s deeply ingrained cultural practices, especially their funerary rituals.

This is not merely the story of a disease but a profound journey of cultural exploration, scientific discovery, and the delicate interplay between tradition and modernity. By unraveling the mysteries of Kuru, we gain a deeper understanding of how isolated communities can shape our collective understanding of health and humanity.

The Fore Tribe: A Community in Isolation

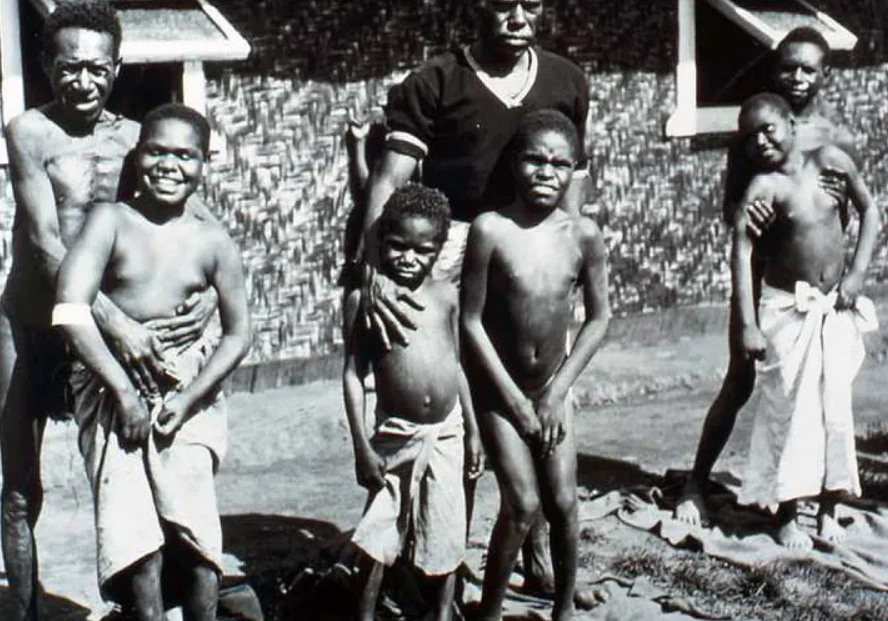

Nestled in the rugged highlands of Papua New Guinea, the Fore tribe lived in relative isolation for centuries. Their remote location allowed them to develop unique customs, languages, and spiritual beliefs. However, this same isolation also meant they were vulnerable to threats that were poorly understood by outsiders.

By the early 20th century, the Fore tribe began noticing a peculiar illness among their members. Initially dismissed as a rare affliction, the disease soon became an epidemic. Women and children—the heart of their community—were dying in alarming numbers. The Fore people attributed the illness to sorcery or ancestral displeasure, a belief rooted in their spiritual worldview.

Understanding Kuru: The “Laughing Death”

The term Kuru comes from the Fore word meaning “to shake,” which aptly describes the disease’s early symptoms. Kuru progressed through three distinct stages:

- Ambulant Stage: Victims experienced unsteady gait, tremors, and difficulty maintaining balance. These early symptoms made everyday tasks nearly impossible.

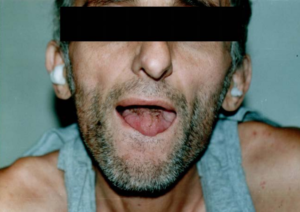

- Sedentary Stage: As the disease advanced, victims lost the ability to walk and developed severe tremors. Emotional instability, including episodes of uncontrollable laughter, became evident during this stage.

- Terminal Stage: In its final phase, Kuru left victims completely immobile. They lost the ability to eat, speak, or respond to their surroundings, eventually succumbing to infections or malnutrition.

For the Fore people, the symptoms—especially the laughter—were a cruel paradox. What seemed outwardly joyous masked the harrowing reality of impending death.

Cultural Practices and the Spread of Kuru

Central to the Fore tribe’s culture was their practice of endocannibalism, a funerary ritual in which the tribe consumed the flesh of their deceased loved ones. This ritual was not an act of barbarism but a profound expression of love and respect. By consuming the deceased, the Fore believed they were allowing the spirits of their ancestors to live on within the community.

Women and children, being the primary participants in these rituals, bore the brunt of exposure to the disease. Unknowingly, they were ingesting the infectious agents that spread Kuru, leading to its disproportionate impact on these vulnerable groups.

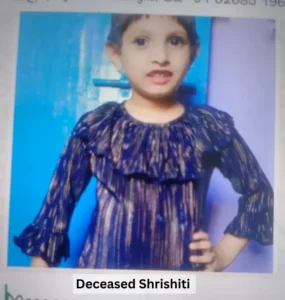

The Journey of Shai: A Heartbreaking Tale

Among those afflicted by Kuru was a young girl named Shai. Her story highlights the devastating personal toll of the disease. Shai was just 12 when her mother succumbed to Kuru. As the eldest daughter, she participated in the funerary ritual, unknowingly sealing her fate. Within a year, Shai began showing symptoms of Kuru herself.

Desperate for help, Shai’s family sought the guidance of Ronald, an anthropologist studying the tribe. However, Ronald’s understanding of Kuru was limited, and he dismissed their pleas as mere superstition. Shai’s condition worsened, and her tragic death became a symbol of the tribe’s suffering.

Scientific Investigation: Unraveling the Mystery

By the late 1950s, the global scientific community began taking an interest in Kuru. Shirley Lindenbaum, an anthropologist, and Michael Alpers, a medical researcher, dedicated their careers to uncovering the disease’s origins. Their initial hypotheses revolved around genetics and environmental factors, but both theories fell short of explaining the disease’s spread.

Through meticulous research, Lindenbaum and Alpers discovered that Kuru was caused by prions, misfolded proteins that could trigger similar misfolding in healthy proteins. This discovery was groundbreaking, linking Kuru to a class of diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), which include Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) and Mad Cow Disease.

Impact of Prion Discovery on Medicine

The discovery of prions reshaped the medical understanding of infectious diseases. Unlike bacteria or viruses, prions lack genetic material, making them uniquely resilient and difficult to treat. This realization spurred new research into neurodegenerative diseases and highlighted the risks of practices like cannibalism, even when culturally significant.

Global Lessons from the Kuru Epidemic

The story of Kuru offers valuable lessons:

- Cultural Sensitivity in Medicine: Effective public health interventions must respect cultural practices while addressing harmful behaviors.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: The Kuru investigation demonstrated the importance of combining anthropology, medicine, and biology to solve complex problems.

- Prion Research: The findings from Kuru have implications for understanding modern neurodegenerative diseases, potentially paving the way for treatments.

The End of Kuru and the Legacy of the Fore Tribe

With the cessation of endocannibalism, the incidence of Kuru dramatically declined. By the late 20th century, the disease had nearly disappeared. However, its legacy endures in the scientific breakthroughs it inspired and the global attention it brought to the Fore tribe.

Today, the Fore people are a symbol of resilience and adaptation. Their story serves as a powerful reminder of humanity’s ability to confront challenges, adapt traditions, and embrace change without losing cultural identity.